Has the time come for a return to supersonic travel?

October 24th, 2003

It is seventeen and a half years since the last ever Concorde flight touched down at Heathrow airport, bringing an end to a twenty-seven-year period when commercial passengers could fly at the edge of space, at more than twice the speed of sound. The story of supersonic flight is one of the very few cases where technology has taken a backward step. The fastest commercial aircraft today flies at less than half the speed of an aircraft that took its first flight 52 years ago.

My career at British Airways overlapped with the last ten years of Concorde’s life. During the second half of this, I was in charge of Network Planning, the department that decides which routes get operated and the schedules that are flown. I was intimately involved in the decision to bring Concorde back into operation after the fatal Air France crash on 25 July 2000, as well as the decision to bring the era of supersonic travel to an end in 2003.

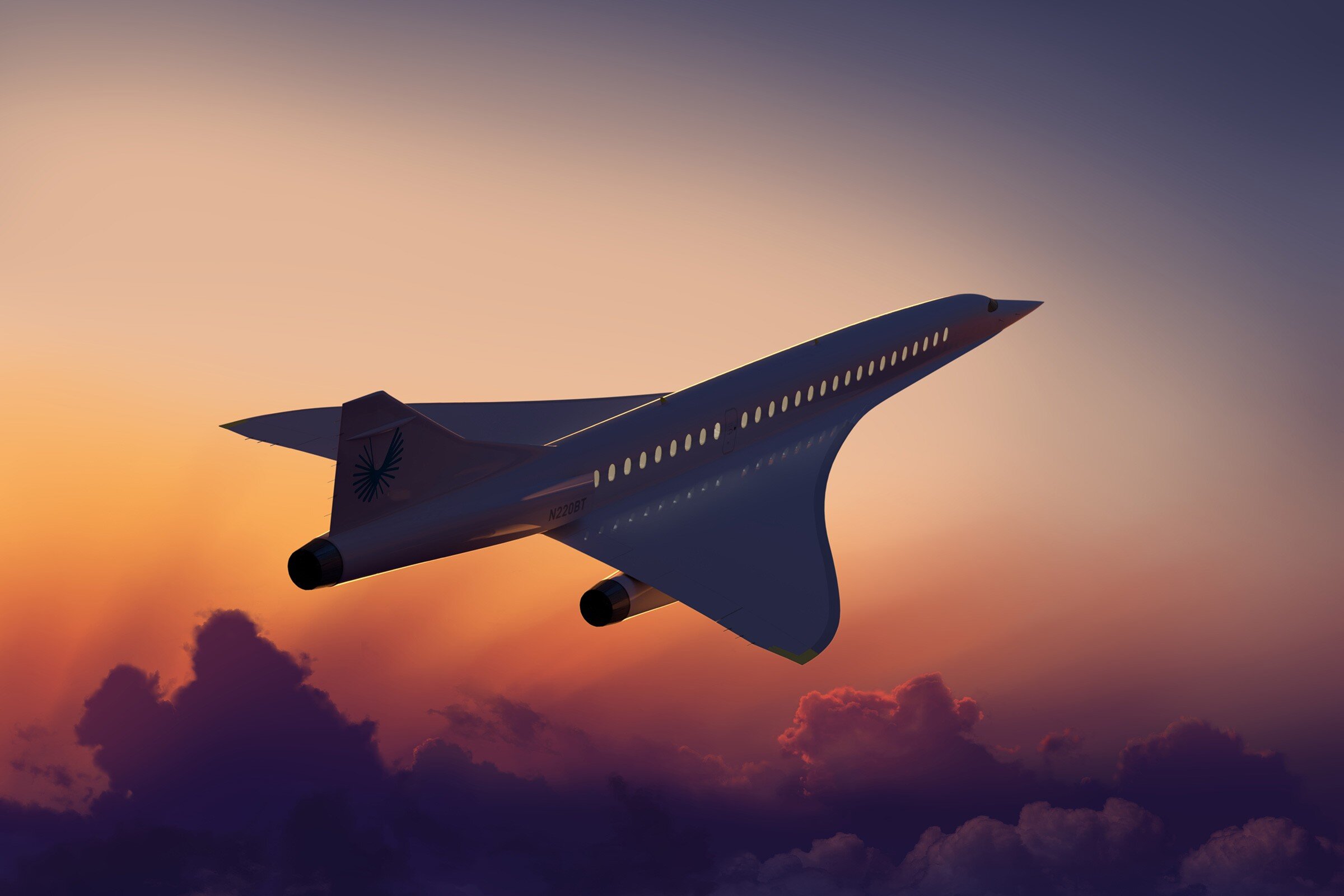

That story deserves more space than I can give it here, and I intend to tell it in a follow-up post. But this post is all about whether the time has finally come for a successor to Concorde, in the shape of Overture from Boom. The reason everyone is talking about it at the moment is because United Airlines has just announced a $3 billion order for 15 supersonic jets from the company, with options for 35 more.

How does Overture stack up against Concorde?

Despite 50 years of technological progress, Overture still doesn’t match up to Concorde when it comes to speed or passenger capacity. Its stated capacity of 65-88 seats is less than Concorde’s 100 seats. Its cruising speed of Mach 1.7 is below Concorde’s 2.04. Its three engines are puny in comparison to the four Rolls-Royce Olympus 593 monsters fitted to the Concorde. With after-burners that were lit up for take-off and punching through the sound barrier, those beasts delivered almost two and a half times the combined thrust of their modern would-be replacements. The design range is a little higher, but this is still a limited range aircraft.

| Concorde | Overture | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Passenger capacity | 100 | 65-88 | |

| Cruising speed | Mach 2.04 | Mach 1.7 | |

| Range | 4,500 miles | 4,888 miles | |

| Length | 205 ft | 205 ft | |

| Wingspan | 83 ft | 60 ft | |

| Engine thrust | 152,200 lbf | -60,000 lbf | |

| MTOW | 408,000 lbs | 170,000 lbs |

I’m sure it will win big on fuel efficiency, reliability and maintenance costs. It could hardly fail to. The stated maximum takeoff weight (MTOW) of 170,000 lbs is only 42% that of Concorde. There’s a reason why it can get away with much less powerful engines. Aerodynamics and materials science have come a long way in 45 years. But it also comes with a $200m sticker price, whereas British Airways and Air France operated Concorde with the benefit of zero ownership costs. Their governments funded the development programmes and ended up gifting the aircraft to their flag carriers due to the lack of demand from anywhere else.

Speed advantage in practice

Overture’s headline benefit is speed. The flight time from New York to Heathrow is advertised as 3:30h instead of 6:30h on a subsonic aircraft.

The first thing to say is that these are obviously flight times, not scheduled block times. To get to those, you need to add taxi-out and taxi-in times. At a busy airport like Newark, taxi-out averaged 18 minutes in 2016, taxi-in was 9 minutes. Then you need to add an allowance for holding times, which averaged 7.5 minutes at Heathrow in the same year. So, you need to add at least 30 minutes to the actual flight times. That’s why United Airlines show a scheduled duration for their current Newark-LHR flights of 7:00h. To state the obvious, Overture isn’t going to taxi any faster than a subsonic aircraft or jump the queues to land.

Can they achieve a 3:30h flight time with a maximum speed of Mach 1.7? Overture will not be able fly supersonic over land, any more than Concorde could. After leaving Heathrow, it had to fly at subsonic speeds until it reached the acceleration point over the Bristol channel, 145 miles west of Heathrow. On arrival at JFK, it needed to have slowed down to subsonic speeds by the time it was 250 miles out from the airport. That’s almost 400 miles at subsonic speeds, 12% of the total journey distance, plus the acceleration and deceleration phases. It took Concorde 75 miles to accelerate up to Mach 1.7 with afterburners on full reheat. Quite how long it will take Overture to do the same with only 40% of the engine thrust is not clear. Of course, Concorde then carried on accelerating up to Mach 2 after it had turned the afterburners off.

Let’s be generous and assume that Overture and Concorde manage 15% of the journey at similar speeds. The lower speed of Overture for the other 85% will mean it will take about 30 minutes longer than Concorde did to fly the route. Concorde’s advertised “block time” between JFK and LHR was 3:45h. That would suggest Overture should have a block time of 4:15h.

Working from subsonic aircraft as a reference, and again assuming the speed advantage only applies to 85% of the distance, Overture should save about 2:15h based on my crude calculations (the reality is more complicated of course, for example allowing for winds). Compared to a reference block time of 7 hours for the subsonic aircraft, that suggests a block time of something more like 4:45h.

If we split the difference, we’d get a block time of 4:30h, saving two and a half hours, or 35%, from the current journey time. I think that’s a better guide than the headlines about cutting transatlantic flying times by 50% would have you believe.

Travellers also need to contend with check-in times, getting through immigration and getting to and from the airport. All of these dilute the saving when considered as a percentage of the overall end to end journey time. Of course, all these areas can be worked on too, as part of crafting a customer proposition all designed around speed. Concorde passengers enjoyed shorter check in times and could board the plane at Heathrow directly from the lounge. But airlines have spent the last decade doing a lot to try to speed up those elements, with mobile check-in and other digital innovations. Premium passengers already enjoy fast track security and priority boarding How much more differentiation can be added for supersonic passengers is far from clear.

What is the business case for saving flight time?

Back in the days of Concorde, the undiscounted ticket price was around £4,000 one way. That was about double the subsonic alternative. The 3:15h time saving therefore worked out at about £600 an hour, something that top professionals could justify, with billing rates for partners in City law firms approaching £1,000 an hour, even back then.

However, the time saving offered by flying supersonic on the transatlantic only really worked in one direction, flying West. Famously, British Airways advertised that you could “arrive before you leave”, with the journey time over an hour less than the time zone difference. Getting on the 10:30 am departure from Heathrow would get you to New York by 09:25, in time to do something close to a full day’s work. Or work a full day in London and take the 19:30 evening flight, arriving in time to go out to dinner with clients or colleagues. Truly a “time machine”.

In the other direction, the time zones work against you. Virtually all the subsonic flights going East are overnight. After a full day in New York, catch the 19:30 flight and arrive at 07:40 the next morning, with time to get to your office in the City or West End for another full day of billing clients £1,000 an hour. That’s why all the investment in recent years by airlines has gone into maximising their premium customers’ ability to sleep. Dine in the lounge before departure and get your head down straight after departure. The 7-hour flight duration from New York is actually not really long enough, especially when the winds are speeding you on your way. Most would prefer the planes to fly more slowly, so they could get another hour or two of sleep.

It is possible to schedule an Eastbound overnight supersonic flight. For Overture, it would leave New York about 21:00 and arrive at Heathrow at 06:30. It is a similar customer proposition to the “red eye” flights from the West to the East Coast of the USA. They got that name because you basically miss a night’s sleep. British Airways never ran a Concorde red-eye service as it would have been worse in almost every way to the subsonic alternatives, preferring to go instead with “daylight” flights Eastbound.

On a market as big as New York to London, there is room for the occasional subsonic daylight flight going East (at least in pre-pandemic times). You leave New York at 07:45 and arrive in London at 19:40. It’s a remarkably civilised flight timing, as your day consists of checking out of your hotel, flying to London and having a quick night-cap before bed. But compared to taking the overnight flight, it costs you an extra hotel night and a whole working day. That’s why it is almost impossible to make such a flight profitable if you are relying on business demand.

It is a little better if you have a supersonic option. Concorde offered two flight timings, a 12:15 departure arriving at 21:00 and a 13:30 flight arriving at 22:25. Both got you back to London in time to sleep in your own bed for returning Brits and bought you some useful extra time in New York. Time for a couple of morning meetings before heading to the airport. But the overnight subsonic aircraft were still generally preferred by business travellers.

One interesting “niche” market that the Concorde was able to serve was the ability to do a day trip to New York. It worked like this. Get the 10:30 flight from London, arriving at 09:25 in New York. Have your important business meeting airside at JFK, using the conference rooms that BA would rent you for just this purpose. After a two to three-hour face to face meeting, take the 13:30 Concorde home in time to sleep in your own bed that night. It sounds crazy, but people used to do it. It was a great way to finalise a multi-billion-dollar deal.

Even if taking a day trip to New York to sign a deal were acceptable in today’s more environmentally conscious world, there is far less need to do such a thing today, given everything that has happened in terms of video-conferencing solutions and digital signatures. In any event, an Overture flight to London would need to leave half an hour earlier (due to curfews at Heathrow), cutting the time available for a meeting. Unless the outbound flight from London was moved half an hour earlier to 10:00, losing valuable connections at Heathrow, you’d lose another half an hour from your meeting time. I don’t see this as a niche that it will make sense for Overture operators to try and serve.

Overall, I can’t see many premium customers choosing an Overture flight going East, even if the price was the same. They will take the overnight subsonic instead. That used to happen with Concorde and the subsonic options have got much better since. That leaves you with an aircraft that only works in one direction from the perspective of its target market. The other direction will be mostly empty or filled with discounted tickets sold to supersonic “bucket listers”.

Market changes since Concorde’s day

British Airways and Air France tried to make Concorde work on many different markets over the years and London to New York was the only one that ever made money. No other market had the sheer market size of premium long-haul travellers to make it work, especially the highly paid bankers and lawyers and the ultra-rich.

Other potential markets were either out of range or would have involved prolonged flying over land where the plane couldn’t go supersonic. That gave it no time advantage and burnt ruinous amounts of fuel. Concorde flew like a brick at subsonic speeds.

Of course, the business market has grown since 2003, leaving aside COVID for a moment. Between 2003 and 2019, international business passenger volumes into and out of the UK grew by 17%. But that’s an average growth rate of only 1% p.a. Even before COVID, new ways of working and environmental pressures were largely offsetting other drivers of growth for a mature market like the UK.

COVID has stamped on the accelerator when it comes to these pre-existing trends. Most people are estimating a 15-20% reduction or worse in business travel volumes compared to 2019, even by the time overall volumes are forecast to have recovered to pre-pandemic levels (c.2025). So, the world in which Overture would be arriving at the end of the decade may not look so different to the Concorde days, at least in terms of overall volumes of business travel.

Many other things have changed since 2003, however. Time spent on an aircraft used to be largely unproductive time for a business traveller. Yes, you had time to read and mark-up documents. If you were travelling in First, you might be able to plug your rather chunky laptop into a power socket to get more than a couple of hours before your battery ran out. But you were cut off from the world (many people are rather nostalgic for those days) and you could make the case to your employer that less time spent on an aircraft had a productivity benefit.

Today’s long-haul aircraft have WIFI and ubiquitous power. The world today is one where most business travellers are easily able to work remotely without loss of productivity. Time on an aircraft, at least in business class, is not unproductive time these days.

By the way, you won’t be getting WIFI on your Overture flight. A satellite dome on the top of an aircraft causes drag. Nobody is going to put one on the top of an aircraft designed to fly at Mach 1.7.

The Boom sales pitch

In recognition of the fact that it will be difficult to get businesses to pay a premium to save a few hours, Boom are pitching the aircraft as being able to offer 50% time savings at the same price as today’s business class fares. We’ve already looked at the time saving part of this. How realistic is the price target?

How many seats will it have?

The first question is seating density. That’s the biggest driver of unit costs.

The “conceptual renders” on Boom’s website show 1-1 seating and one seat row per window.

Looking at the exterior shots of the aircraft (below) and measuring the window spacing relative to the stated length of the aircraft, I calculate a seat pitch of 47 inches if it is one row per window. That’s more generous than Concorde’s 37-inch pitch, and Concorde was 2-2 seating as well.

There are 27 windows. So, with a 1-1 layout and one row per window, that is 54 seats. We are still missing 11 seats from even the lower end of the 65-88 seat stated capacity. Is there really room for five windowless rows at the rear of the aircraft, or in front of the main door? Plus a singleton opposite one of the exits? That’s what would be needed to bring the total up to 65 seats. We also need to find some room for toilets and galleys somewhere and remember that we need to fit an engine into the back of the main fuselage.

If there really are 33 rows pitched at 47 inches squeezed in there somehow, that gives a length for the passenger seating area of 125 feet, 67% more than Concorde had with 25 rows pitched at 37 inches. That is for an aircraft with almost exactly the same overall length. Admittedly, Concorde probably had more space devoted to galleys, closets and toilets than might be deemed strictly necessary nowadays (see LOPA below). The cockpit also needed space to accommodate a flight engineer, which won’t be needed now. But overall, I am left unconvinced that the real-world seat count will be anywhere near 65 seats, if the on-board seating experience is anything like the marketing photos.

The seating density matters a lot, because that is really the only area where a supersonic aircraft has the opportunity to offset the intrinsically higher costs of flying faster. Because people will be on-board for 4.5 hours, rather than seven and the flights will be daylight rather than overnight, you can get away with less space.

Concorde had seats that were 17.76 inches wide and pitched at 37 inches. Compared to a standard economy seat with 17.6-inch width and 31-inch pitch, that is only 20% more space per person. That helped Concorde offset the fundamental operating cost disadvantage it had versus business class seats on the 747.

BA’s latest business class seat on the A350-1000 has 27-inch-wide flat bed seats pitched at 79 inches. On the face of it, that uses 3.9 times the space of an economy seat, but given the angled 1-2-1 configuration, I think it is more like 3.3 times.

I don’t know what the seat width is in the Overture marketing renders, but they look pretty wide to me. If they are the same width as the BA Club World seat (27 inches) pitched at 47 inches, that’s 2.3 times an economy seat. That would give Overture a 30% saving in space per seat compared to a flat-bed subsonic seat.

30% less space per person is never going to compensate for the cost penalties of flying supersonic. Overture haven’t published anything on expected fuel burn, but this 2018 study by the International Council on Clean Transportation estimated that the Boom reference design would likely burn 67% more fuel per unit of passenger space than the ICAO CAEP/10 standard reference for subsonic aircraft. The fuel efficiency of subsonic aircraft that will be delivered in the same timescale as Overture would be better than the reference, of course.

Other costs

Of course, fuel is not the only operating cost. Most unit costs in aviation go down with aircraft size and Overture will be a small long-haul aircraft by any standard. It will need the same number of pilots as an A350-1000, which carries more than five times the number of passengers and a lot of cargo too. Maybe United is going to pay their supersonic pilots less than their other international crew for the privilege of flying a supersonic aircraft? Good luck with that.

It is also worth discussing aircraft and crew utilisation. In theory, you could get a saving in crew costs coming from the time saving of flying faster. You only need to pay for 4:30h of crew costs rather than 7:00h. But in practice, crew are not going to be able to do two supersonic sectors in a duty period. There will be no one or two-hour flights to mix into the roster. Overture crew will not be cross licenced on other fleet types. This is going to be a very unproductive fleet from the perspective of flight hours per head.

There is a similar problem with aircraft utilisation. You would think that by flying faster, you could get more trips out of an aircraft each day. A supersonic aircraft could do three or four long-haul sectors a day, rather than two. Since this post has already gone pretty deep into airline geekery, I’m going to go through some aircraft rotations to show why that isn’t going to happen in practice, at least for a fleet doing only transatlantic trips.

Aircraft utilisation

Let us start with a subsonic example. I’m using BA flight schedules from 2007, since I was amused to find that the last timetable BA ever published in PDF form is still available on its website, and we are all enjoying a spot of nostalgia here.

Our story starts with a 747-400, commencing its day at Heathrow. Maintenance had it overnight, but operations manage to extract it from their clutches in time to operate the 08:20 flight to JFK, which arrives at 11:00. It takes a couple of hours to refuel and have its turnaround checks. But it needs to sit around anyway, waiting for the first evening flight back to Heathrow, which leaves at 18:25. That flight will get to LHR at 06:25, so it can’t leave much earlier. If it did, it would arrive before LHR opens at 06:00. At Heathrow, it could just about do a turnaround and head back to New York at 08:20, but in practice it will more likely operate a slightly later flight. However, this example demonstrates that London – East coast US flights “turn on themselves”. To operate one daily flight, you need one aircraft, more or less. You can easily get 14 hours of aircraft utilisation from a subsonic schedule. You’ll lose a bit for maintenance downtime, but you’ll gain some back by mixing in longer flights to the West coast or elsewhere in the world.

Now let us look at the London – New York Concorde schedule which ran from about 1991 until the crash in 2000.

| Flight | From | To | Depart | Arrive | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BA001 | LHR | JFK | 10:30 | 09:25 | 03:55 |

| BA003 | LHR | JFK | 19:30 | 18:25 | 03:55 |

| BA002 | JFK | LHR | 12:15 | 21:00 | 03:45 |

| BA004 | JFK | LHR | 13:30 | 22:25 | 03:55 |

We start once more at Heathrow, with the BA001 departing at 10:30. We arrive in New York before we’ve left at 09:25. As with the subsonic example, we have time to deplane the passengers, refuel, clean and cater the aircraft, then board the passengers before heading back to London at 13:30. We arrive back at base at 22:25 the same day, but too late to operate anything else. This aircraft managed 7:50h of daily utilisation.

The second aircraft hangs around London all day, probably being fixed by Engineering, whilst it waits to operate the 19:30 flight, arriving in New York at 18:25. The next flight out of JFK is the following day at 12:15, getting back to London at 21:00. This aircraft has managed 7:40h of utilisation in two days. It didn’t get back to Heathrow in time to operate the 19:30 departure, so we need three aircraft to run this twice daily schedule, with an average daily utilisation of 5:10h. BA actually had seven aircraft, with one used to provide a “hot standby” and the other three lost in maintenance due to the legendary unreliability of Concorde. But they were on the books for nothing, so not a big deal.

Overture shouldn’t need so much maintenance and the flights will be half an hour longer, but less than six hours a day of aircraft utilisation even without standby cover would be a big issue if you’d had to pay anything like the $200m sticker price that Boom are asking for. I’m sure all you airline schedulers out there will be convinced you could do much better and maybe you could if you want to add in some loss-making red-eye flights. But you’ll never get anything close to 14 hours a day. You can probably manage to come up with a schedule that matches the subsonic pattern of one aircraft per daily transatlantic trip. But trust me, there are no cost savings here unless the aircraft can operate some non-transatlantic trips to utilise ground time at either end.

At the European end, that would mean the Middle East, Africa or Asia. But if the aircraft can’t fly supersonically over land, those don’t work.

At the US end, we’re talking the Caribbean, South America or the Pacific. The Caribbean would work, but it is probably too close to get much advantage from the speed and I don’t see the premium market sizes being big enough.

The bigger markets in South America like Sao Paolo and Buenos Aires are at the edge of or beyond the range (4,758 miles for Sao Paolo, 5,290 miles for Buenos Aires). They would also involve flying over land.

Which brings us to the big question mark, the Pacific. Many of the city pairs referenced on Boom’s website are Pacific trips. We’ll look at that next, but I should point out that any Pacific flying that United Airlines does with its Overture aircraft will be out of its West Coast hubs. Those flights are not going to integrate from a scheduling point of view with the transatlantic operation and will not therefore do anything to rescue the transatlantic aircraft utilisation or crew productivity figures.

The Pacific

The Boom website lists several Pacific route examples. I’ve shown the time saving figures they claim in the table below and have added the great circle distances for each route.

| Route | Overture | Today | Distance (miles) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tokyo – Seattle | 4:30h | 8:30h | 4,769 |

| Los Angeles – Sydney | 8:30h | 14:30h | 7,488 |

| Los Angeles – Seoul | 6:45h | 12:45h | 5,994 |

| San Francisco – Tokyo | 6:00h | 10:15h | 5,124 |

The claimed range for Overture is 4,888 miles, so only the first of these is technically within the non-stop range of the aircraft. A 2.5% margin of error for range based on manufacturer claimed figures is not something that any airline planner would consider remotely a serious prospect. Maybe a more detailed technical study looking properly at wind conditions and so on might conclude that it will work, but I’m not buying it.

The other examples are all well beyond the non-stop range of the aircraft. I assume that the claimed Overture flight times allow for a refuelling stop somewhere en-route. I think they are based on stops in Anchorage or Tahiti. Both would involve a detour from the great circle route and additional take-off and landing costs. Any fuel uplifted from the mid-point will be priced at a premium, especially if it needs to be Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF), a topic to which I will return shortly. Having your journey split into two 3-4 hour sectors will not be conducive to being able to sleep, even if you have a seat that is comfortable enough to make that a possibility.

I am deeply sceptical.

Sustainability

I’ve left the elephant in the room until last. We saw earlier that the fuel burnt per premium passenger was likely to be significantly higher than a business class seat on a modern subsonic aircraft. Boom is claiming that they will be able to match that benchmark. The only way I can see that happening is if they cram more seats on the aircraft. Concorde showed that you can get away with quite a small amount of personal space if the rest of the package is right. But that is not the on-board experience they are showing you in the marketing materials.

Both United Airlines and Boom clearly know that sustainability is their Achilles heel and are trying hard to head off that criticism with claims that this will be the world’s first zero-carbon aircraft.

The Boom website is full of lovely words. “Our vision is to make the world more accessible. It’s fundamental that we take care of it, too”. “A more sustainable future of travel”. “The world’s fastest and most sustainable airliner”.

United Airlines’ press release said: “United continues on its trajectory to build a more innovative, sustainable airline and today's advancements in technology are making it more viable for that to include supersonic planes”.

How stupid do they think we are?

The claims that this will be a “zero carbon” aircraft seem to be based on Overture offsetting the carbon involved in its manufacture and the fact that it will be designed to operate with 100% SAF. The topic of SAF is a complex one, but there are two things you need to know.

Firstly, any aircraft can operate with SAF. It is designed to be a “drop in” replacement which can be blended with conventional fuels. Every aircraft is an aircraft that can operate with 100% SAF. Secondly, the things that are standing in the way of transitioning the world’s aviation to SAF are economics and supply constraints.

I hope I’ve already demonstrated that operators of Overture aircraft are not going to be in a unique position to afford to pay a premium for SAF. The aircraft will also burn more SAF per passenger mile than their subsonic equivalents. In a SAF supply constrained world, that is bad for the environment. Don’t get me started on the likelihood of having a large supply of SAF available at an affordable price in Tahiti any time soon.

So far, I’ve only talked about the direct carbon costs of burning fuel. There is also the issue of aviation’s non-CO2 impacts on climate change. Although not well understood, the substantially higher altitudes at which supersonic aircraft operate (60,000 feet compared to 35,000-40,000 for subsonic aircraft) are believed to be more damaging to the environment.

To finish off this look at Overture’s sustainability credentials, it will clearly be noisier than best in class subsonic aircraft too. We know that’s the case because Boom have been lobbying for a change in US law to exempt them from current noise limits.

In summary

Much as the aviation geek in me would love to see the age of supersonic travel return, I can’t see the economics working. Maybe it would work on a handful of routes, but there is no way Boom is going to have a viable programme on that basis. The smaller the global fleet, the higher the costs of supporting the aircraft, especially one as unique as Overture will be. Niche aircraft tend not to survive.

As if that wasn’t enough, the environmental case seems to be a showstopper.

In my opinion, United Airline’s announcement of an “non-firm” order is a blatant publicity stunt. Their attempt to portray it as compatible with a commitment to sustainability casts grave doubts on that commitment.

Many of United Airline’s shareholders are genuinely committed to an ESG agenda. I think they should be asking United’s CEO Scott Kirby to explain what on earth he thinks he is doing.