Prospects for a third runway at Heathrow

The long-running saga continues

The first time a UK government approved the building of a third runway was all the way back in January 2009. Gordon Brown was Prime Minister. The iPhone was still something of a novelty. The average cost of a pint of beer was £2.69, 40% lower than today. In truth, the argument about whether and where to build additional runway capacity in the South East had already been running for decades, with endless studies looking at the issue but no decisions taken.

Of course, the 2009 decision was reversed by David Cameron after the next election. My understanding is that he gave a commitment to do so as part of winning support from local Conservative MPs for his party leadership bid. Sadly, national infrastructure projects have always been something of a political football in the UK.

The issue of what to do about runway capacity in the South East hadn’t gone away, so more time and money was spent on yet another review which in 2015 concluded that Heathrow was still the right option. That was endorsed the following year by the government, although it took two more years to receive parliamentary consent. The plan was challenged on legal grounds and found unlawful in 2020. That decision was appealed by Heathrow and the ban lifted later that year. By that time, we were in the middle of a pandemic, so the plan sat on the shelf gathering dust until January 2025, when the government once again endorsed moving forward.

Despite everything that has changed over the last 16 years, the issues at stake remain much the same as they were in 2009. Then, as now, expansion was generally supported by business but opposed by environmental groups, with noise, local air quality and carbon emissions all front and centre of the debate.

Back in 2009, all the airlines were supportive of the government’s strategy. The low-cost carriers weren’t interested in Heathrow, but they were kept happy with the decision announced at the same time to support a second runway for Stansted, which was to open ahead of expansion at Heathrow. But the position of airlines has changed somewhat over the years, mainly due to the spiralling cost of the project. One of the reasons the government likes the idea of the runway expansion is that it won’t have to pay for it, unlike other major infrastructure investments. The airlines of course are rather less keen on the idea of being landed with a bill of £40 billion or more, even if it does get recovered over many years.

I thought it would be interesting to look back on how the case for the third runway has changed over time. So let’s jump in our time machine and look at what was proposed 16 years ago.

The regional runway plan

Back in 2009, the proposal was for a 2,200-metre runway that could be fitted into largely empty land to the north of the airport, dramatically reducing the number of houses that would need to be demolished compared to a “full length” runway.

Although considerably shorter than Heathrow’s two existing runways, which are both over 3,500m, it would have been longer than Luton airport’s runway and considerably longer than the 1,500m runway at London City airport. I estimate that at least 60% of Heathrow’s existing flights could happily take off from that length of runway and an even higher percentage could land on it.

The cost of the scheme was estimated at £7.8 billion, which would be equivalent to £12.2 billion today after adjusting for inflation. That’s less than a third of what the latest proposals are now forecast to cost.

Perhaps the cost of the short runway plan was underestimated, but it is undeniable that it was a more modest plan that could have been developed at lower cost, with fewer houses needing to be demolished and without needing to move the busiest motorway in Europe into a tunnel. It would have delivered essentially the same increase in movements and passenger numbers, albeit with less operational flexibility than a longer runway.

Before moving on to the more recent expansion proposals, I think it is educational to review the assumptions that were being made back in 2009 to justify the need for expansion. How well have they stood the test of time, with the benefit of hindsight? Let’s start with passenger demand.

Passenger numbers forecast

The Department for Transport (DfT) projected that in an “unconstrained case”, passenger numbers for the UK as a whole would grow from 241m passengers in 2007 to 410m by 2025, in their central case assumptions. That’s about a 3% annual growth rate. For 2030, they projected 465m passengers. For a scenario where no additional runway capacity was added (“constrained case”), the central forecast was for 375m in 2025 and 405m by 2030.

How does that compare with what has actually happened? Well for 2024, total passengers through UK airports were only 295m. That’s an annual average growth rate of only 1.2%. Of course, the pandemic is part of the story here, but much higher aviation taxes and emissions charges have also played their part. Seat capacity is projected to grow by 3.6% in 2025, so we might reasonably expect to get to 306m passengers in 2025. That will leave us 18% below the government’s constrained projection for 2025.

Whilst that might seem to undermine the case for growing capacity, the shortfall has all come from outside the London area. The “no additional runway capacity” projection for London area airports in 2030 was 185m. Passenger volumes have already hit 177m in 2024, so all it would take to hit the 2030 forecast would be 0.7% p.a. growth.

Perhaps it is unsurprising that London area passenger volumes are remarkably close to forecasts made 16 years ago, given that they have they have been heavily constrained by capacity restrictions. The shortfall in non-London volumes might be a better indicator that underlying demand growth has been much weaker than expected back in 2009.

However, lower growth rates had also already been recognised by the time runway expansion was approved by Parliament in 2018. As part of that decision-making process, the DfT published forecasts in early 2017 for passenger numbers of 295m in 2025 and 315m in 2030. Despite the huge and unanticipated hit from the pandemic, those forecasts now look to have been on the low side if anything.

Emissions

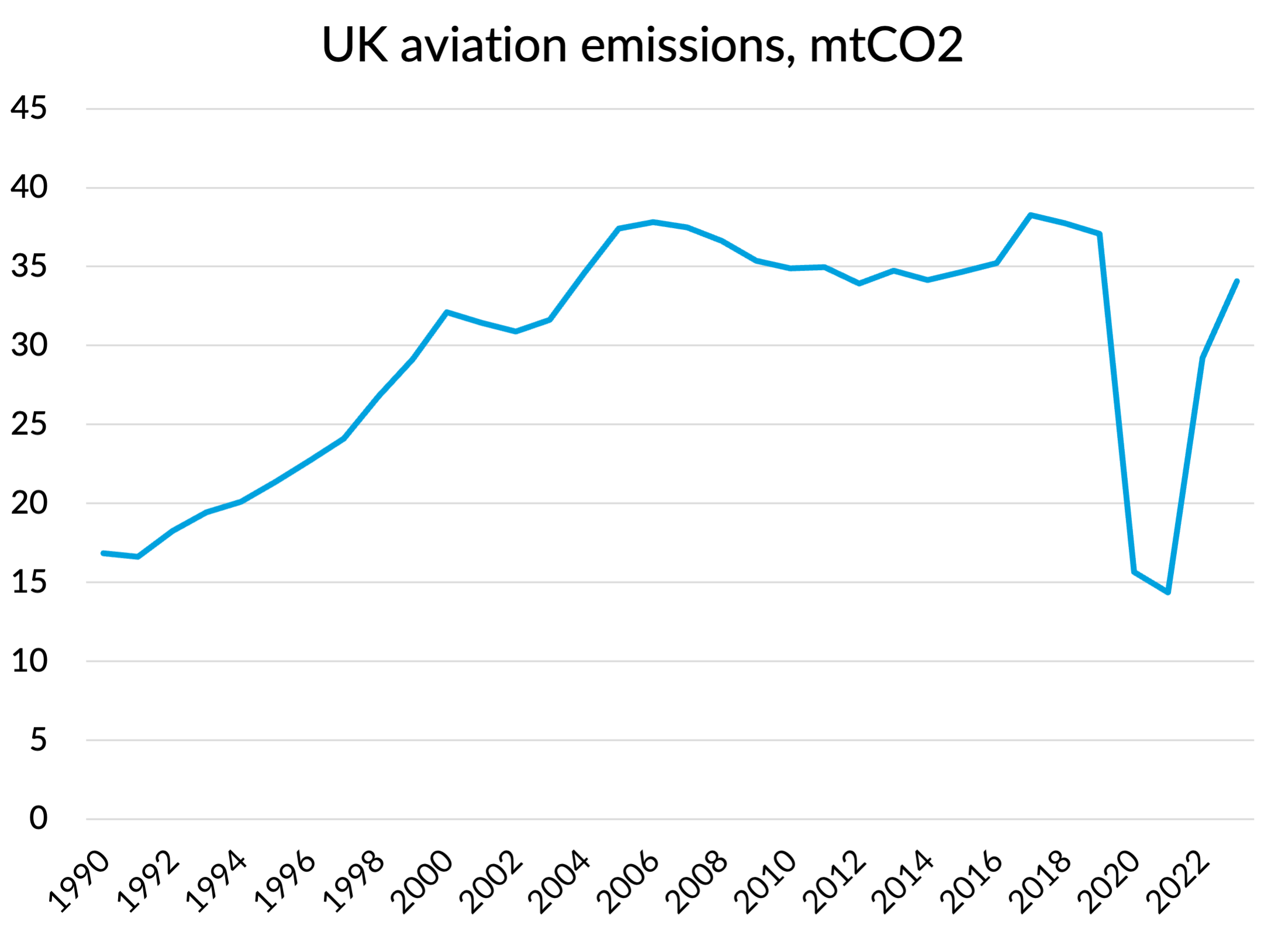

One of the things in the 2009 government decision that had environmental groups reaching for their lawyers was the projection for carbon emissions. From a base of 37.9 million tonnes of CO2 in 2006, aviation emissions were forecast to grow to 58.4m tonnes by 2030 if the Stansted and Heathrow runway expansions went ahead as proposed. Even without runway development, emissions were projected to grow rapidly to 53m tonnes by 2030.

This is one of the areas where things have changed dramatically since 2009. The actual emissions in 2023 were in fact only 34.1m tonnes. Instead of growing rapidly, they are actually 10% below the 2006 level, despite passenger numbers being 16% higher. As we’ve already seen, some of the shortfall is due to lower passenger growth than forecast outside London. But the industry has also made much faster progress on efficiency than was assumed 16 years ago.

Source: UK government statistics

The industry is also well ahead of efficiency forecasts made by the DfT as recently as early 2017. Those envisaged a central case for emissions of 38.6m in 2030. On a per passenger basis, the 2023 actual emissions were within 2% of that figure, with seven more years of efficiency improvements still to come.

These figures are also gross emissions. With a good chunk of aviation emissions now covered by trading schemes, there is a good argument that on a net basis the outperformance has been a lot higher.

DfT’s carbon emissions forecasts in 2017 made little allowance for SAF. In their baseline, they assumed that uptake would reach 5% by 2050, with <0.5% in 2030 and only around 1% even in 2040. Those assumptions now look weirdly conservative, given the UK SAF blending mandate of 2% in 2025, rising to 10% in 2030 and 22% in 2040. Heathrow reported that 2.5% of fuel uplifted at the airport in 2024 was SAF. An assumption of 50% was used for carbon savings from SAF compared to fossil fuels, which is also super conservative.

Granted, a third runway was forecast to increase emissions by about 8% compared to the “do nothing” baseline and 2050 emissions were 2% higher than their 2020 projection. But given how much better emissions have been than the DfT projections, it seems likely that when these projections get updated the picture will look a lot better.

Noise

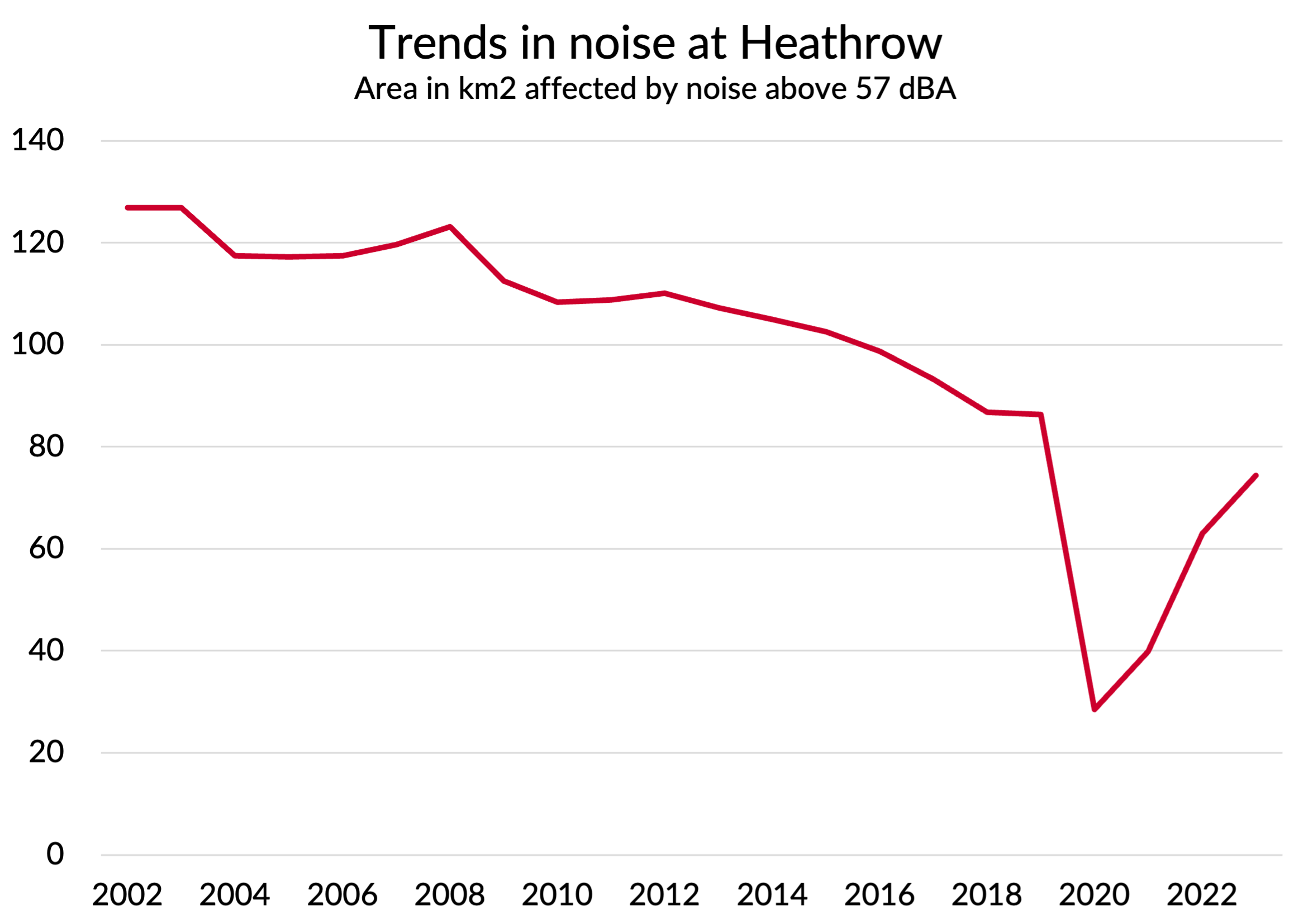

Noise has long been a contentious issue for Heathrow expansion. Back in 2006, the government expressed its view that there should be “no net increase in the size of the area of the 57 dBA noise contour beyond its 2002 position (127 km2)”. However, it also said that given on-going improvements in aircraft noise levels, the development of a third runway need not be incompatible with that.

Of course, no runway was built and the continued march towards quieter aircraft has meant that by 2023 the area of land affected by those noise levels has in fact dropped by 40%. There is still quite a bit of noise reduction to come from replacing older aircraft with the current generation of quieter aircraft, and next generation aircraft will be quieter still. I am sure that a third runway could be accommodated within the current noise footprint. But local residents would of course still prefer to see the faster reductions that would come without expansion, and a new runway will change the geographical distribution of noise, so there will undoubtedly be people who would see an increase in noise if the runway gets built.

Source: CAA statistics

Future growth without runway capacity

Heathrow has grown passengers by an average of 1.1% per annum over the last 20 years, despite the lack of additional runway capacity. Could that trick be repeated again over the next twenty?

It doesn’t seem likely to me. Almost half of the increase has come from load factor increases. Although average aircraft size has growth by 0.6% p.a., part of that has come from the on-going migration of slots from short-haul routes to long-haul, which on average are flown with bigger aircraft. The acquisition of short-haul airline bmi by British Airways was one of the key enablers here.

Average aircraft size on long-haul flights has actually declined marginally. There has been a 0.7% p.a. increase in average aircraft size on short-haul, but again there is more to this than meets the eye. A good chunk of this is has come from densification of existing aircraft.

All of the past mechanisms by which Heathrow has continued to eke out growth without runway capacity have natural limits. Load factors are now at record highs. There isn’t another bmi for BA to acquire. There are only so many seats you can pack onto an aircraft.

There is some potential for up-gauging of short-haul aircraft at Heathrow and at other airports. At Stansted, Ryanair is switching from 189 seat 737-800 aircraft to 197 seat 737 Max 8-200s and will also bring in the 228 seat 737 Max-10, if certification issues can be resolved. But given the time that will take, it is hard to see that accounting for more than 1-2% p.a. growth overall. Other large operators like Wizz are already mostly flying the biggest aircraft variants available.

It is also a fallacy that restricting frequency growth through limiting runway capacity will automatically get compensated by growth in aircraft size. The UK may be an island, but it does compete for traffic with other countries, many of which are continuing to grow flight numbers and develop their hubs. It the UK continues to stand still, growth will go elsewhere.

For me, there is no escaping the fact that supporting annual growth of more than 1% or so is going to require additional runway capacity somewhere in the South East.

The business case for the third runway today

It shouldn’t be a surprise that airlines are more cautious about the business case today than they were back in 2009. The cost has at least tripled, even after adjusting for inflation. More of the environmental costs are now “internalised” through emissions trading schemes and the costs of moving to SAF.

During the last consultations, Heathrow offered generous compensation schemes to local residents (adding to the cost of the project) and proposed tightening restrictions on night flights and early morning arrivals. My estimate at the time was that after taking account of those new restrictions, the third runway wouldn’t actually increase early morning arrival capacity at all. That is precisely the area where Heathrow slots are the most scarce and valuable. Most long-haul flights need an early morning arrival slot, and short-haul flights also need one if they are to be useful for connecting passengers. Touted as a solution to the need for more “hub capacity”, the actual expansion proposal we ended up with didn’t do a good job of delivering that from a runway capacity perspective.

About the only thing that Heathrow airport and the airlines seem to be able to agree on at the moment is that a third runway will require a change to the regulatory system. For the airport, that means they need to be able to get more from airlines and their customers than the existing system would permit. For the airlines, it means the precise opposite. Some tinkering with the charges formula might help to spread the cost over a longer period. But the only way to really square the circle is to reduce the cost of the scheme. Finding options which avoid the need to put the M25 into a tunnel might be a good place to start.

Do the sums add up?

The UK is already a mature aviation market and ticket prices already face upward pressure from rising emissions charges and the cost of SAF mandates. That won’t be an easy environment in which to pass on higher airport charges, if that is what is needed to pay for the runway. Higher prices for customers would also depress demand at a time when the airport will be looking to grow.

So although the key battle ground of getting a third runway through planning might appear to be mainly about the challenge of meeting the environmental conditions, I think it will be affordability question that will be the biggest hurdle to overcome. Back in 2017, Heathrow promised that it could keep landing fees “close to current levels”, despite expansion costs. Airlines will be pushing hard to see the same commitment honoured, if Heathrow expansion does go ahead.