Ryanair’s aircraft cost advantage

How much does Ryanair pay for aircraft?

As I’ve pointed out in previous articles such as this one, Ryanair always comes out as best in class when it comes to aircraft ownership costs. Some of that might be driven by accounting policies, as I explored in that article. But I think a lot of it is down to the aircraft deals it has done over the years with Boeing.

How much does it pay for its aircraft? Only Ryanair and Boeing really know the answer, but I think we can come up with some decent estimates by reverse engineering the numbers from their accounts. So that’s what I decided to do.

Let us start with a little history on Ryanair’s fleet and the various orders that the company has placed with Boeing over the years.

737-800

Back in 1998, Ryanair was operating a fleet of just 20 737-200s. The huge orders for 737-800 aircraft which it was to place over the following seven years would see those aircraft quickly replaced and also underpin a massive growth in the airline to the 500 aircraft behemoth we see today.

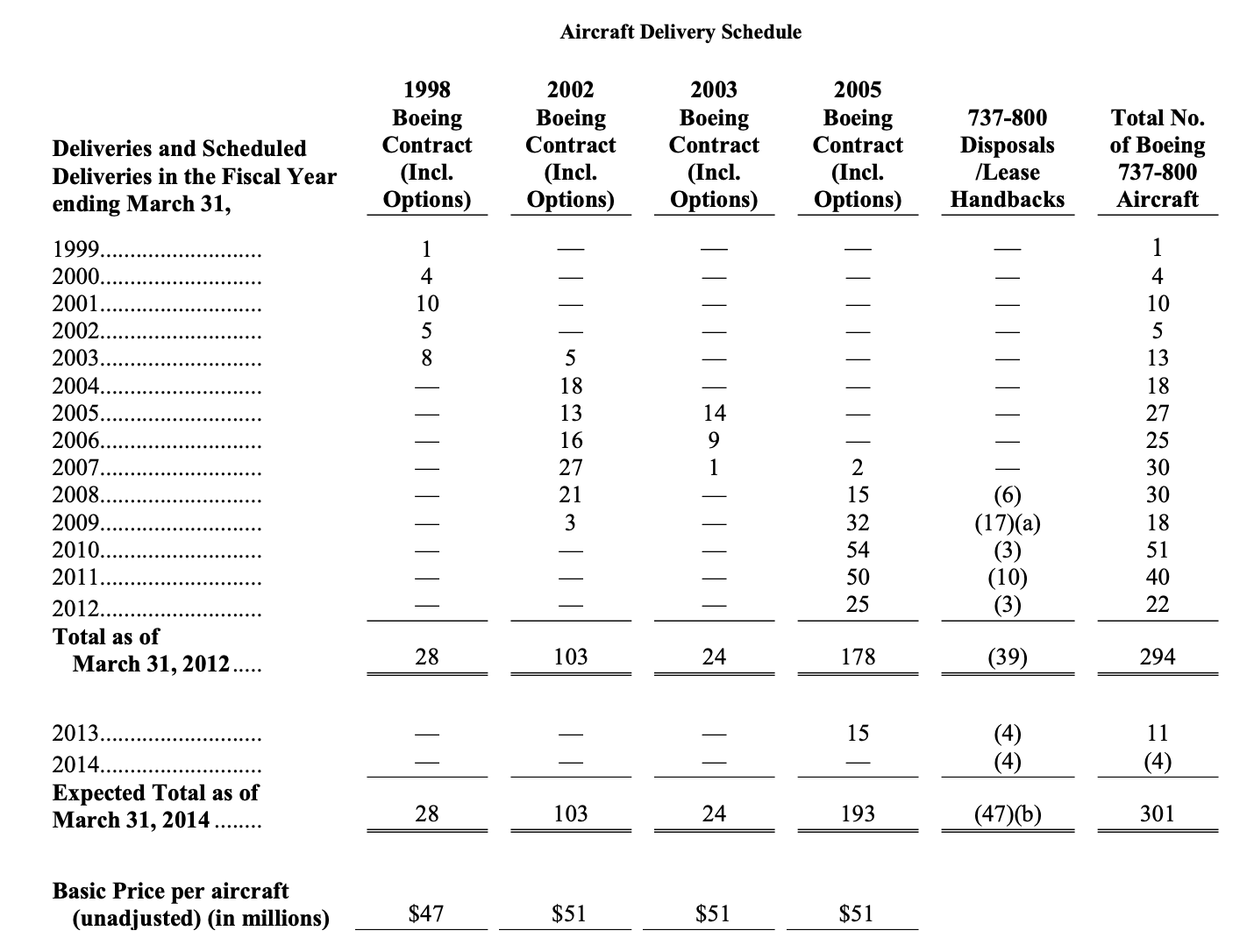

The first order was placed in March 1998 for 25 aircraft, plus options for 20 more. Four years later in January 2002, it significantly increased its commitment, with another order for 100 aircraft, plus 50 options. Only one year later, it ordered another 22 aircraft and also secured a significant increase in the number of option aircraft to a total of 125. In February 2005, another order was placed for 70 firm aircraft plus 70 options and that deal also reset the terms for the aircraft still to be delivered from earlier contracts for all deliveries from the start of 2005. Those options were progressively exercised during the following four years and some additional top-up aircraft were added too under the same contract terms.

There was to be one further order for 737-800s in 2013, but before we get to that I am going to start my analysis by looking at the terms of the 2005 contract. Of the 531 aircraft that Ryanair would eventually buy from Boeing, 55% (297 aircraft) were covered by the terms of this contract. There is a useful table in the 2013 accounts which gives a good summary of the deliveries associated with the first four contracts.

Source: Ryanair annual report, March 2013

What was the price paid under the 2005 contract?

We can get an upper bound for the price paid for the 270 aircraft delivered between April 2005 and March 2013, all of which would have been under the terms of the 2005 contract, by looking at Ryanair’s capital expenditure on aircraft assets during that period. The figures were are all reported in euros of course, but I’ve translated them into dollars at prevailing exchange rates for the period in the analysis which follows.

At the end of March 2005, Ryanair reported a total of $379m of advances for aircraft, all of which must relate to future deliveries of 737-800s. The capital expenditure on aircraft during the following eight years added up to $6.9 billion and by March 2013, with all the deliveries made, the company reported no advances outstanding. So we know that those 270 aircraft cost Ryanair less than $7.3 billion. I say “less than”, because any heavy maintenance expenditure during that period would also have been included in the aircraft capital expenditure figures.

How big could those heavy maintenance costs have been? Ryanair says that major checks for their 737-800s typically occur between 8 and 12 years. At the start of the period in question, none of its aircraft were more than 8 years old. By the end, 51 aircraft would have hit an age of 8 years but only 5 would be 12 years or older. And as we saw from the above table, between 2008 and the end of March 2013, Ryanair disposed of 43 aircraft, almost certainly aligning the disposals with the first major checks coming due. So I think that the spend on major maintenance which might be included in the capital expenditure for aircraft was probably minimal during that period.

With that assumption, we can work out the average price paid per aircraft of $27.1m. You will see in the table above a figure of $51m for the “basic price” of the aircraft. Ryanair says that this is the list price referenced in the contract, excluding BFE (buyer furnished equipment). Ryanair said that BFE would add $900k per aircraft. The actual price they paid would be that basic price, escalated in line with agreed inflation indices up to 18-24 months before delivery, less big credits from Boeing and the engine supplier, otherwise known as discounts.

Even the $51m figure is very far from what the list prices for the aircraft would have been at the time of delivery. The earliest list price figure I can get hold of for the 737-800 is from 2000, when Boeing quoted the list price as between $53.0 and $60m, depending on configuration. Even if we assume that the Ryanair figure is based on the cheapest configuration and therefore at the bottom end of the range, I think it must be a figure which dates from 1998, the date of their first contract. I’ve escalated that figure using an average of the US Employment Cost index and the US Producer Price Index (the two metrics referenced by Ryanair as being used for their escalation clause). That would give an average escalated “basic price” for the aircraft delivered over these eight years of $70.9m, suggesting that Ryanair obtained a 62% discount compared to that reference. If you used the actual list price for the aircraft in the years they were delivered (a cool $80.1m), the achieved discount would increase to 66%.

737-800 prices - the “2013 order”

We can repeat the above exercise for the last 737-800s that Ryanair ordered from Boeing. Those relate to a deal done in 2013, for 175 aircraft. Within a year, that had been topped up to 180 aircraft and in the end 183 aircraft were delivered over the 2015 to 2019 period.

By this time, Ryanair’s fleet was older and so I’ve made an estimate for the annual capital expenditure related to major maintenance on the rest of the fleet of €200m per annum. That’s the figure they spent on aircraft capital expenditure in the year ending March 2014, adjusted for the movement in advance payments. This was a year when they took no deliveries. That gives me an estimate for the average price paid of $35.8m per aircraft, an increase of 32% on the average price paid for the 2005 order, albeit on average delivered 7-8 years later.

Ryanair gave a figure for the “basic price” including BFE for this contract of $81m. Applying escalation as before gives an average escalated basic price 18-24 months before delivery of $81.7m. That’s not much of an increase because US Producer Prices were actually falling around that time. That would work out at a discount of 56% against that reference, suggesting a worse deal. But it is quite likely my crude estimate for the escalation doesn’t match the reality of the contract - in particular I doubt that Boeing would permit a negative escalation factor to be applied. Against a reference of the average Boeing list price at delivery, the discount works out at 65%, much more comparable to the level of discount we saw before.

MAX aircraft

What about the new generation 737 MAX 200 aircraft, or the “gamechangers”, as Ryanair rather annoyingly insists on calling them?

In their financial year ending March 2022, Ryanair took delivery of 61 aircraft and recorded fleet-related capital expenditure of €1.6 billion. Again, we need to adjust for movements in advances, which fell from €507m to zero (no figure for advances was given for March 2022, which I assume wouldn’t have been allowed by the accountants if it was a material amount). If we again allow for €200m p.a. of major maintenance spend on the rest of the fleet, that would give us a price of $38.8m per aircraft, allowing for the fact that Ryanair hedged their capital expenditure at much better rates than the market. That’s only 8% higher than we got for the cheaper 737-800 and would represent a discount to list price at delivery of 69%.

How big an advantage does Ryanair have versus the competition?

Only Boeing, Airbus and the airlines concerned know what discounts they achieve. It is harder to do equivalent “outside in” analysis for other airlines, most of which order a mixture of aircraft types and don’t provide the same level of disclosure about advances, which significantly muddies the waters. Ryanair is also unusual in purchasing all its Boeing fleet. Other airlines acquire a lot of their aircraft using leases, which complicates things too.

I’ve seen estimates for Boeing’s average discount level of 47%, although that work dated from a few years ago and was an average across all aircraft types and geographies. Based on my own experience, I think a 50% discount to list price is a good “rule of thumb” for a decently sized airline making a significant order. The biggest airlines with negotiating leverage will do better, of course. If Ryanair is getting 65%+ discounts and competitors are only getting something like 50%, that’s more than a 30% advantage in acquisition costs. Given that residual values will be the same for all airlines, based on a 23 year life, the advantage in depreciation costs would be even bigger at 35%+. If aircraft are turned over faster, the depreciation advantage is better still.

It is probably the case that the 737 MAX prices for the early aircraft are “distorted” by the compensation deal Ryanair agreed with Boeing for the long delivery delays. But it certainly does look like Ryanair’s 737 MAX deal has ended up being an incredibly cheap one and will help the company sustain its aircraft cost advantage over the next few years.

Longer term challenges

Ryanair has set out an ambition to fly 225m passengers in its 2026 financial year. It says that is based on a fleet of 620 aircraft. We know that 149 of them will be 737 MAX aircraft, assuming Boeing can deliver them in line with the contract. But where are the rest coming from?

We know that the airline would like to have increased their MAX order, but were unable to gain agreement from Boeing at the price that Ryanair was looking for. Given the eye-watering discounts that we’ve seen for earlier orders, you can understand why Boeing is unwilling to come to the table on the kind of terms that Ryanair expects. Airbus is unlikely to step into the breach - there is history of bad relations there going back to a time when O’Leary switched back to Boeing after verbally confirming to Airbus that they they had won a fleet competition. In any case, Airbus has more demand than supply for its A320 NEO family at the moment. There is no way they would be willing to meet Ryanair’s price expectations.

So unless either Boeing or Ryanair backs down on price, Ryanair is going to have to work with the aircraft it has, plus what it can secure in the market. By 2026, the oldest 737-800s it still has in its fleet will be reaching 22 years of age, well past the 18 year mark at which previous 737-800s left the fleet. It also has 27 leased Airbus A320 aircraft, operated by Lauda Europe. They are 15 years old on average, so they can keep flying for a while. But even if it keeps all 409 737-800s going, that still leaves a gap of 35 aircraft to meet its 2026 ambition. For an airline that likes to maintain a homogenous fleet, that might be a challenge. When it finally starts to replace the 737-800s, it will need another 20-30 aircraft a year and even a 5% annual growth rate equates to something like 30 aircraft a year for an airline of Ryanair’s size.

So I think it will be hard for Ryanair to maintain both its growth ambitions and its aircraft cost advantage. Boeing is obviously betting that eventually Michael O’Leary will be dragged back to the negotiating table with more “realistic” expectations about price.

Ryanair’s competitors will be hoping that he instead opts to reign in his growth ambitions.